In the days before fresh produce was available in supermarkets year-round, a root cellar was an essential part of every home. They're a lost way of life and were once a crucial link in the subsistence chain. In one form or another, we may need to rely upon them once more -- this time after the pole shift. Conditions might render a root cellar a luxury, but it's an option we should be knowledgeable about.

Let's take a look at key points from the book "Root Cellaring" by Mike & Nancy Bubel. I'd consider this one a must-get, and I purchased my copy through the Barnes & Noble web site.

The authors found with proper planning they could produce about 33 kinds of vegetables for winter storage.

- Vegetables store best if harvested at the peak of maturity. This takes a little planning.

- Many storage vegetables grow best in the cool growing days of fall.

- Unblemished, disease-free vegetables keep best.

- Well-fertilized kale, collards and cabbage contain more vitamin C than those grown on lean soil.

- Whole grains will remain in good condition for two or three years if kept cool and dry and protected from insects. Pick a tightly closed container that shuts out light and that insects and rodents can’t penetrate. Grains don’t belong in a damp root cellar.

- Cured meats, especially ham and bacon, can be kept in a root cellar if the temperature is 40° or below. (About 4° C)

- You can even put potting soil in the root cellar over the winter so it won’t be rain-soaked when you need some for spring seedlings.

- Root vegetables can be left in the ground until hard frost, and that way the temperature in your root cellar is more likely to be at an optimal level.

- It shouldn’t be necessary to clean most vegetables, but handle with care and store only your best. Curing isn’t necessary for most root vegetables.

- Leafy tops of parsnips and beets are good to eat.

- Lowering the storage temperature is the single-most important thing you can do to promote the longevity of root vegetables.

- The optimal temperature for most root vegetables is around 32° F (0° C)

- The majority of storage vegetables are biennials -- those that go to seed after a winter dormancy period. Nature intends them to last the winter.

- Store enough items so that a few losses won’t matter.

- Inspect your stored vegetables weekly.

- The main cause of shriveling in storage is low humidity.

- The authors also discuss outside storage of vegetables in mounds, also known as clamps. However, I couldn't find a web site that dealt with this topic.

- If you’re willing to dig a hole for it, an old refrigerator can provide good storage space for vegetables. You bury the refrigerator to take advantage of the moderating and more constant temperature of the sub-surface soil. Keep the refrigerator well covered and protected from moisture, and you may need to install a vent.

- If winters are mild (average temperatures over 30° F) you won’t be able to reach the optimum temperature in a root cellar. In this case, the vegetables should keep well in a heavily-mulched garden row.

- In planning a root cellar, temperature is the first consideration. You want to maintain temperatures at 32° to 40° F (0 to 4 C).

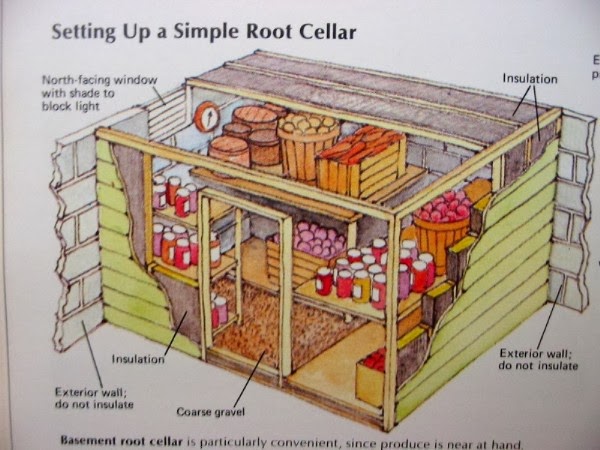

- Double-doors or a small anteroom (fore-room) provide an additional degree of protection from temperature swings. Insulation also helps maintain a stable temperature. You can use sawdust, wood shavings, cinders, straw, even dry leaves. Some outdoor-survival books discuss how to keep insulation dry.

- The next requirement is high humidity, about 90% to 95%. This will help prevent the food from shriveling. You can measure humidity with a hygrometer, though humidity shouldn’t be a problem in a post-shift world. If the cellar has a dirt floor, it will provide natural moisture. If necessary, you can place water in shallow pans. You can also pack root vegetables (especially carrots, beets, and parsnips) in damp sawdust, sand or moss to reduce surface evaporation. If you can install one, an arched ceiling will cut down on condensation problems.

- You also need proper ventilation, and this means installing a low air-intake opening and a high air outlet on opposite sides of the room. In Europe, the pipes are often insulated to help prevent condensation. Don’t place your storage shelves right against the walls. Your food can get moldy. Ditto if you place your storage bins right on the floor. A palette-type device is recommended.

- The storage room should be kept dark.

- You want to clean up the cellar annually.

- Crates utilize space more effectively than baskets.

- A space eight-by-eight feet (about 2.5 square meters) should be plenty for the average family.

- Root cellars are too humid for canned goods, unless you consume these in perhaps the first year.

- You don’t want a strong draft through the bin, because this will remove moisture from the produce.

- If the outdoor temperature is higher than the root cellar, keep the air-intake vent closed during the day.

- If it’s extremely cold out and the cellar is reaching below 32° F, you can put some hot coals in there to warm things up.

- Store only your best vegetables.

- Keep them as cool as possible between harvest and storage.

- Dug-in root cellars work well because they are insulated by the earth surrounding them. The soil is a poor conductor of heat, so the temperature of the ground six feet under the surface is cool and fairly constant. The natural moisture of the earth helps to keep humidity high. It is important to provide drainage around the cellar so there is no water-logged soil to freeze and cave in the walls.

- You can cover a dirt floor with gravel, but you don’t want a concrete floor. You also want a drain to allow excess water to seep out. Cover it with a screen. Excessively rainy conditions may call for a trench.

- In many places, most root cellar crops can be safely left in the ground until November.

- Keep carrots and beets away from any condensation that might by dripping from the ceiling.

- If mice become a problem, you may have to screen individual containers of vegetables.

- One enterprising person made a root cellar out of a discarded truck which he drove into a dug-out hillside.

- If you don’t have a thermometer, you can put a container of water in the cellar. If it starts to freeze up, you’ll need to warm up the cellar somehow.

- Incidentally, a root cellar can make an excellent shelter from tornadoes and hurricanes.

- Old-timers sometimes built the front wall of a root cellar twice as thick as the back wall.

- You need a good roof that doesn’t allow moisture to penetrate the cellar. If it’s structurally sound, you can place a couple feet of dirt on it for additional insulation.

- Apples: I don’t foresee growing these, but they’re considered the ‘queen’ of storage fruits.

- Beets: good keepers. The ‘Long Keeper’ variety is just that -- a great keeper. The leaves are vitamin-rich. Can last 4 to 5 months in storage.

- Brussels sprouts: might keep 4 to 5 weeks if kept in perforated plastic bags. This reminds us we might want to stock up on plastic grocery bags for this purpose.

- Cabbage: if it splits, it won’t keep.

- Chinese cabbage: can last up to three months. You can even replant them in a box of soil in the root cellar.

- Carrots: a summer planting is best for winter keeping. They are the backbone of any food-storage plan. The roots are rich in vitamin A and they can last several months in storage. With adequate mulching, you can even keep them right in the garden row for the winter.

- Cauliflower: keeps only a short time at best, two to four weeks.

- Celeriac: a good keeper.

- Celery: see how late you can keep this in the garden, and then maybe you can get a month or two of storage out of it.

- Garlic: needs lower humidity than root vegetables. If you can find a cool, dry place, it can last seven or eight months.

- Horseradish: very hard and a good keeper.

- Jerusalem artichoke (sunchoke): can last several weeks in plastic bags or in damp sand.

- Kale: high in vitamin content, easy to grow, extremely cold-hardy.

- Kohlrabi: the leaves are good to eat. Packed in damp sand or sawdust, it can keep well into the winter.

- Leeks: especially cold-hardy. Can make it through a winter outdoors if well mulched, or you can plant some in your root cellar in tubs of sand or soil.

- Lettuce: has a short storage life.

- Onions: seed-grown onions are especially good for storage.

- Parsnips: these are perhaps the hardiest of all root vegetables. Be sure to dig them out. If you pull them, you can lose half the root. If you nick the roots with the shovel, don’t store them. Nicks and blemishes invite spoilage, and this applies to all root vegetables. For longer storage, pack them in damp sawdust. Leaves, moss, or sand will work well too. The leaves are edible.

- Sweet Potatoes: the roots are vitamin-rich, and they can keep several months if stored well. Must be cured.

- White Potatoes: beware of planting the kind you buy in the store -- they may contain disease. Cool nights promote storage of starch, making for a longer-keeping potato, so the later-maturing ones are best for storage. Must be cured and kept in a dark spot. They can last four to six months.

- Pumpkins: those that have lost their stems won’t keep well.

- Winter radishes: they’ll last until February if well stored.

- Rutabagas (Swedish turnip): will last two to four months in storage.

- Squash: if it’s well stored, it will keep for up to six months. Cure them for 10 to 14 days. Like pumpkins, keep them dry and moderately warm.

- Tomatoes: late-planted tomatoes are best for storage.

- Turnips: these are among the hardiest of vegetables. In storage they might put out pale, leafy tops, good for stews.

MMORPG

ReplyDeleteinstagram takipçi satın al

Tiktok Jeton Hilesi

tiktok jeton hilesi

saç ekimi antalya

Instagram Takipçi Satin Al

instagram takipçi satın al

MT2 PVP SERVERLER

instagram takipçi satın al

perde modelleri

ReplyDeleteNumara onay

VODAFONE MOBİL ÖDEME BOZDURMA

nft nasıl alınır

ankara evden eve nakliyat

trafik sigortası

dedektör

web sitesi kurma

Ask kitaplari

smm panel

ReplyDeleteSmm panel

iş ilanları

instagram takipçi satın al

hirdavatciburada.com

Https://www.beyazesyateknikservisi.com.tr/

Servis

tiktok jeton hile

yurtdışı kargo

ReplyDeleteuc satın al

en son çıkan perde modelleri

en son çıkan perde modelleri

minecraft premium

özel ambulans

lisans satın al

nft nasıl alınır